Author Sylvie Bigar is a New York food and travel writer who went to France on a magazine assignment to write about Cassoulet. Ten years later, that assignment led to her latest book, Cassoulet Confessions: Food, France, Family, and the Stew That Saved My Soul.

It’s a beautifully written book that’s part literary memoir and part travel journal; and it paints a rich picture in words as she literally unlocks the secrets of Cassoulet (a French stew) and explores the Swiss, French, and Jewish cultures that shaped her life.

The book is now available on Amazon and Audible!

Listen to the podcast on Apple and Spotify!

Here’s Elaine's Q&A with Sylvie. You can also watch it on YouTube or listen to the podcast on Apple or Spotify!

Here’s Elaine's Q&A with Sylvie. You can also watch it on YouTube or listen to the podcast on Apple or Spotify!

Elaine: Everybody here knows that we like to celebrate the people, places and food behind the stories. And today I want to introduce you to Sylvie Bigar. She has written a book called Cassoulet Confessions. And I just couldn’t wait to share it with you because it’s a memoir. It’s about food and family and France. And it just had so much wrapped up in one book that I thought it was just right in line with what we like to share with everyone.

So, Sylvie, thank you so much for being with us today.

Sylvie: Thank you. Thank you very much for inviting me. Thank you for reading the book.

Elaine: Yes, I loved every word!

One of the chefs you mentioned in your book told you that cassoulet has almost fostered its own religion. Talk to me about how you got involved with cassoulet to begin with and how that story became so much more.

Sylvie: I want to disagree with you. I think that everybody can make cassoulet! I feel like I’m in Ratatouille. You know, everybody can cook, right? So what is cassoulet? Maybe it’s good that we just describe the dish a little bit first.

Basically, cassoulet is a stew. It’s an uncomplicated, rustic stew, and the base of it is beans. And it doesn’t have to be particular beans. You have plenty of beans in Texas, wonderful beans. And there are many recipes for cassoulet.

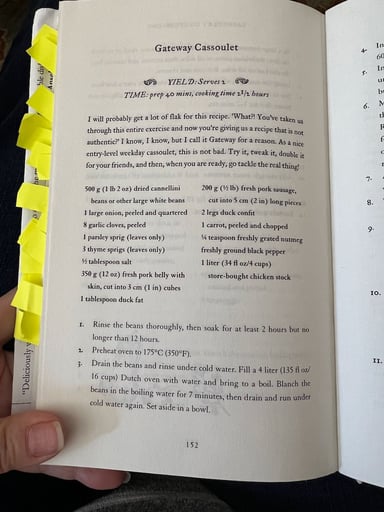

But there are three master recipes, just like there are a few master recipes for French sauces. So usually it’s duck confit, which is duck cooked in its own fat, pork, sometimes lamb, and beans, herbs and a lot of garlic and pigskin as well. This is not a light dish, but everybody can cook cassoulet. In my book, I have a recipe that takes three days, and then I have what I’ve called Gateway Cassoulet. The Gateway Cassoulet is in the September issue of Food and Wine. It’s a recipe that is easy and that you can start in the morning and then you’ll have your cassoulet by the end of the day.

Elaine: Lovely description! And it makes it seem almost doable!

Your book reminded me that words can be really beautiful. They can paint pictures, they can write songs. So it was a really great reminder that there is there is a better side of writing.

Sylvie: Sometimes, I think all that’s really needed is to let the magic happen. Because the truth is, I went to the southwest of France on an assignment. I was working as a food and travel writer and I was assigned a story on the history of cassoulet.

Now, you may know that there are a few of these iconic French dishes. There’s chocolate in the north, there’s bouillabaisse in the south, which is a kind of fish and shellfish stew. And then, of course, we all know Julia Child’s boeuf bourguignon. Cassoulet is one of those iconic dishes.

I’m actually originally from Switzerland. French is my first language. So I thought I would just would go there, and report on my story, come home, write the piece, get my check and move on.

I’m actually originally from Switzerland. French is my first language. So I thought I would just would go there, and report on my story, come home, write the piece, get my check and move on.

In fact, what happened is that this one-week trip back in 2008 changed my life. Why? Because I encountered real magic.

Elaine: And so how do we help people do the same thing? So we love publishing cookbooks, whether it’s an individual with a family history and special recipes that they want to capture in a book, or it’s a chef or a food business owner who wants to share their experiences and showcase their recipes. We always encourage them to share stories — not just share recipes or photos — but really dig deeper and share the stories behind the food.

What tips can we give people when it’s time to start writing and sharing the stories behind the food?

Sylvie: I think we all start in the kitchen and I think we all start with the family. It’s not always rosy, it’s not always good memories. But I think that a lot of our taste memories are imprinted as children, and sometimes it’s painful to go back there. And sometimes people have forgotten what happened. Were they scolded because they tasted grandma’s chocolate mousse? Or what happened?

I think we can all say that we love recipes, but we also love stories. Right? We love human stories. We love drama, we love poetry. And all of these genres start, I think, in childhood.

Elaine: Yes, even as a marketing guide, we rely on stories. And we always say, when there’s conflict, the story gets interesting. I want to tell people, “Don’t hold back when it comes to sharing the hard things — the things that might be a little bit painful — because that’s when you really show that human connection and something that we all have in common.”

Sylvie: Exactly. While I was writing Cassoulet Confessions, I found plenty of conflict. In France, you know, chefs and cooks have very definite ideas of how things should taste, how things should be cooked, or not. And in my book, we go to the extreme, because there’s also the whole story of what kind of pot is the right clay pot to cook the cassoulet. And people actually almost fight, physically, about things like that. And there are several different shapes of clay pots.

I’ve been working with a company in Minnesota called Clay Coyote, and they’ve created the perfect cassole — that’s the name of the pot used to cook the cassoulet.

Elaine: I can’t wait to look it up! Speaking of culture, let’s dig in there for just a second. We’ve all got things that happened in our childhood that we’re were really connected to. And then you’ve got the French take on many things versus what we may experience here in the US.

In the book you talked about Christmas versus Hanukkah and your experience as a child, wanting to be part of Christmas, but then really loving and appreciating your own culture, the traditions.

Many of us don’t necessarily have a history of these rich traditions in the same way that you might have had in the Jewish faith. I’m going to read just a short paragraph from the book:

At school, I hated feeling different, but I enjoyed the traditions we followed at home. One gift for each of the eight nights of Hanukkah, the Winter Festival of Lights, the pure pleasure of wedging my tongue through the salted butter and thick honey I layered on a matzo cracker, the unleavened bread eaten at Passover. Heading to the synagogue to hear the deep baritone of the young rabbi on Friday nights.

Those are the things I wish we shared more; the feelings and experiences that we can take time to appreciate in each other. So, while I don’t think I have similar experiences, that one paragraph connects me to you and to the Jewish faith in some small way. And I love having that bit of insight and understanding.

Sylvie: Thank you so much for saying that. It’s interesting because it seemed as though when I when I started writing that, you know, so many of my experiences would be sort of different and people wouldn’t be able to relate. And in fact, what I’m what I’m realizing is that we all have these universal feelings, right?

So I had matzo with honey, but you had your Christmas cookies. You have the Thanksgiving turkey, but Thanksgiving is not celebrated in Europe. So, I mean, the first time I tasted a sweet potato casserole, you know, when everybody at the table is just saying… they’re all, you know, in heaven. And I’m and I’m thinking, this is strange, this is sweet, but it’s a vegetable.

Elaine: One of my quotes in the dessert cookbook that I did is about sweet potato pie is: Only a southern, true southern woman would turn a vegetable – a sweet potato – into a pie. And but it is one of my favorites. I don’t usually care for sweet potatoes, but I love my mother’s pie. That’s a good memory, too.

Talk about the sort of the French culture a little bit, because I think in the US we have this stereotype of the French culture and you’re describing how they could even come to blows over the proper way to make certain things. So how accurate is the stereotype of the “French Chef” and what did you discover that was a little different than you expected?

Sylvie: I’m not really sure which stereotype you mean, but I’ve done a lot of work with Chef Daniel Boulud (actually, I wrote his latest cookbook, Daniel: My French Cuisine). I’ve spent a lot of time in the kitchen of his flagship restaurant in New York City. And I’ve seen French chefs, in action. So, I think the stereotype is — and please tell me if you think I’m wrong — is maybe the image of the chef who is bossy and maybe knows exactly what he wants. And it can only be one way.

And I think Americans sometimes get a little self-conscious about not eating the right way or not knowing which utensils to use because there’s three different forks next to the plate, things like that.

I was not interested in any of this in Cassoulet Confessions. I’m interested in traditions, ingredients, authenticity. I mean, the epitome of slow food, really, the stew, you know. And the only thing that matters is, how does it taste? Do you like it? Do you love it? You love it? I love it. That’s it. Universal, you know, feelings. That’s really all I was looking for.

Elaine: And I think the other thing I took away from it was not only these excellent ingredients, beautifully prepared. It’s the slowing down. It’s slower in the kitchen and the way it’s prepared, yes, but it’s also slowing down at the table to appreciate that time together and the flavors there. Because I think Americans tend to just shovel it in, you know, and then move on to the next thing. Whereas, whether it’s cassoulet or another beautifully prepared meal, it can become an experience. And I think taking the time to enjoy that experience is a really good takeaway.

Sylvie: I think so. And I think Julia Child spoke about that all these years ago… the

importance of taking the time to enjoy. And I think we saw this even in the movie. Julie and Julia, right?

Elaine: We did. That’s a good reminder. So let’s talk about you. Other than cassoulet, what dishes are you known for?

Sylvie: I make a good lamb shank, actually; and I love, honestly, the recipes of Mark Bittman because they are very simple. They never fail. And so you can use them as a base. You know, there’s a there’s a New York Times lamb shank recipe where I think he has four ingredients: salt, pepper, olive oil and lamb shank. And I love that because in a way, I look at that as a blank canvas. And then you can add things. You know, something that I love to add, for example, with lamb is orange zest. It seems as though I always go back to slow cooking.

Elaine: I can see why! Tell me, again, other than cassoulet, what is your most memorable meal?

Sylvie: My most memorable meal at home was the tarragon roasted chicken that we made often and that I always requested on my birthday. And it’s the perfect roasted chicken. And I think roasted chicken has a bad rep in the States, I think it’s often considered, as you know, maybe it’s you get a piece of chicken meat and three sides in the in the south, you know, something like that. And but the way… I hate to say this again… but the slow way that you can roast a chicken with herbs, tarragon, particularly, is a really good, good combination. That’s something I love.

Elaine: Sounds delicious. And once again, I am instantly hungry.

Sylvie: Actually, that is my other goal in life is that people will say maybe at some point, “You made me hungry.”

Elaine: Well, I think you did that many times in your book! So for those of us who want to crawl out there and try making cassoulet… You said you’ve got a simple version in the book that we can start with.

Sylvie: Yes. So I would say start with what I called the Gateway Cassoulet. It’s on page 152. The prep time is about 40 minutes and the cooking time is only two and one half hours.

Elaine: Nice.

Elaine: Nice.

Sylvie: So do this. Take a Sunday and do this; get your ingredients in advance. And I think that the goal is that at the end of the meal, you’re going to want to go back and take the longer recipe.

And then you’re going to want to see the difference between the two.

Elaine: I am definitely going to try it and I will keep you posted.

Is there anything else that you just wish people knew? And that’s a big blanket statement. It can be about food, about France, about New York…

Sylvie: Since you are in the business of helping people write their books, I’m going to tell you that I think we all have stories to tell. And I think we know what these stories are. It has not been an easy road. It took me about ten years to write 154 pages, which is kind of a joke. And so what I want to say is, don’t get discouraged. Don’t get discouraged. Keep going. Don’t get discouraged by the letters of rejections. We had a lot of letters of rejections, but at the end of the day, you have a story to tell. And there’s probably a lot of us who want to read that story.

Elaine: Thank you for that! That’s such good advice as we wrap up. So where can people find your book?

Sylvie: Everywhere! Everywhere. In the independent bookstores that we all love around the country. But then, of course, on BarnesandNoble.com and Amazon. Right. And IndieBound and where all the good books are sold.

Elaine: I will be sure and share links so people know how to find the book. Thank you again for being with us today. This has been great and I just wish you so many more food journeys to come!